Building Resilience in Long-Cycle Biopharma Innovation

SUMMARY: Established in 2009, COBIK – the Centre of Excellence for Biosensors, Instrumentation and Process Control – has become a central actor in uniting regional academic and industrial partners to address pressing health challenges. From its inception, COBIK combined leading research with a strong commitment to building a functional innovation ecosystem. Over time, its efforts increasingly concentrated on biotechnology and biopharmaceutical processes, positioning COBIK as a pivotal actor within both the Slovenian and international innovation landscape.

In 2021, the Biopharma Global Connect Cluster (BGC) was officially launched as a specialised spin-off initiative within COBIK, created to take on cluster-oriented tasks that extend beyond the remit of a centre of excellence. However, the origins of BGC trace back to 2007, when an informal collaboration between entrepreneurs and a university laid the foundation for COBIK’s establishment. Supported by UNIDO and the Slovene Enterprise Fund, BGC’s mission is to act as a central hub where challenging biotechnology projects – in biopharma, food, environment, and agriculture – can progress seamlessly from idea to market, regardless of their maturity stage. BGC enhances the ecosystem anchored by COBIK by addressing the shared needs of its members, such as building trust-based networks and partnerships, enabling joint projects, facilitating access to funding and infrastructure, supporting technology transfer and regulatory navigation, and boosting international visibility.

COBIK’s and BGC’s activities play a pivotal role in overcoming some structural barriers. As the Northern Primorska (Goriška) region lacks political autonomy, the organisations have managed to hurdle missing support structures on a regional level by pooling resources, coordinating efforts, and strengthening international links. Together, they secure the regional biotech and biopharma community’s connectivity, competitiveness, and international relevance. Currently BGC has identified a number of strategic international projects and is preparing for a structured internationalisation phase in the coming year, aimed at deepening cross-border knowledge exchange and further reinforcing its role within the global cluster landscape.

Northern Primorska Region (Goriška)

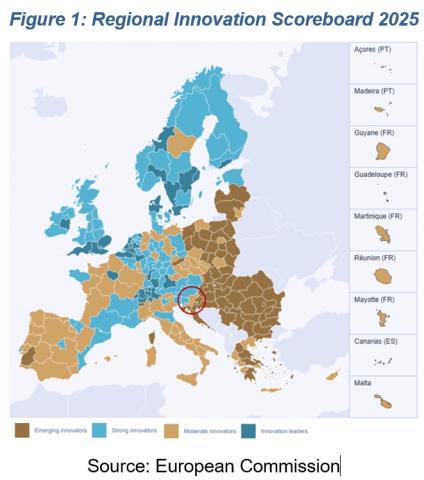

The Northern Primorska region is geographically diverse – ranging from narrow valleys to wide plains – and strategically located at the crossroads of Italy, Austria, and Slovenia, with strong logistics links and proximity to major ports in Trieste and Koper. It borders Friuli Venezia Giulia (Italy), one of the most economically powerful Italian regions. Northern Primorska is not an official administrative but a historical-cultural region in Slovenia’s coastal and western areas, spreading across the country’s statistical (NUTS 3) region Goriška. However, it is part of Western Slovenia, which, together with Eastern Slovenia, forms one of the country’s two NUTS 2 administrative regions. Although Slovenia’s regions have no political autonomy and are instead governed on a national and municipal level, they display notable contrasts in terms of innovation capacity and economic indicators. Western Slovenia is characterised by a strong innovation performance, especially when compared to its Eastern counterpart, which is considered a moderate innovator by the EU Regional Innovation Scoreboard (see Figure 1). This disparity stems primarily from the concentration of research institutions, universities, and advanced industrial hubs – particularly in manufacturing sectors such as automotive components, electronics, and pharmaceuticals – which are predominantly located in and around the capital Ljubljana and the coastal areas of Western Slovenia.

In Eastern Slovenia, GDP per capita is around EUR 27,900, and the proportion of residents with tertiary education reaches 84% of the EU-27 average. By contrast, the more densely populated Western Slovenia significantly surpasses both benchmarks (GDP per capita of EUR 42,800 and 110% relative to EU-27). Investment in R&D is also unevenly distributed, with public sector R&D expenditure in Western Slovenia reaching 116.4% of the EU-27 average – 16.4% above the EU standard – while Eastern Slovenia allocates only 15.1% of the EU average.

Western Slovenia and also the Northern Primorska region (spanning 13 municipalities, i.e. Nova Gorica, Ajdovščina or Brda) are home to several recognised higher education institutions, including the public University of Nova Gorica, some faculties of the Primorska University as well as the private New University and the School of Advanced Social Studies in Nova Gorica (SASS). Despite the presence of these academic centres, collaboration between academia and industry remains limited, with untapped potential for stronger integration in research, innovation, and technology transfer.

Northern Primorska’s traditional economic strengths lie in advanced manufacturing, metal processing, automation, green technologies (including renewable energy, hydrogen, and circular economy), tourism and creative industries, as well as agri-food, viticulture, and niche high-tech sectors such as photonics, mechatronics, biotechnology, and instrumentation.

Building on these strengths, the Knowledge Park in Ajdovščina – Biotechnopolis is planned to be one of Slovenia’s most ambitious innovation hubs, combining education, research, and high-value industry in one location. Strategically situated near the regional airfield with strong links to Ljubljana, Koper, and Italy, it will host universities, research centres, incubators, and industrial facilities, with a focus on biotechnology, aeronautics, hydrogen, and green and digital technologies that align closely with Northern Primorska’s specialisation priorities.

Alongside its research and industrial base, the park will also include a science and innovation centre, an aviation museum, sports and leisure areas, and conference and hospitality facilities. By clustering education, science, business, and community life, the project aims to stimulate regional growth, attract investment, create quality jobs, and position Northern Primorska as a European hub for sustainable, technology-driven development[1].

[1] ECCP Clusters Meet Regions Slovenia 2025, Input Paper.

Western Slovenia’s economy is primarily service-based, with the service sector employing 69.2% of the workforce. While this share is below the EU average, it remains substantially higher than in Eastern Slovenia (60.2%). Industry also plays a particularly prominent role, accounting for 23% of employment – well above the EU average of 17.5%, though still below Eastern Slovenia’s 28.5%.

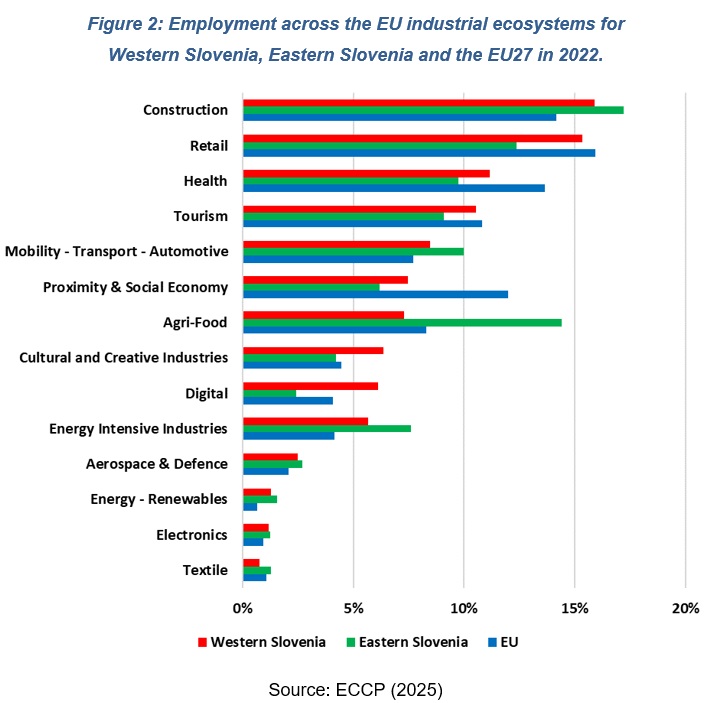

Within the 14 industrial ecosystems identified by the European Commission, Construction emerges as the largest employer in Western Slovenia with 15.9% of total employment (see Figure 2). This is followed by Retail (15.4%) and Health (11.2%). Among these, only Construction surpasses the EU average, though it still remains below Eastern Slovenia’s share. In addition, the region shows comparatively strong employment in Cultural and Creative as well as Digital industries, with shares exceeding both EU and Eastern Slovenian levels. [1]

At the same time, Western Slovenia’s employment shares in Mobility-Transport-Automotive, Energy Intensive Industries, Aerospace and Defence, Energy-Renewables, and Electronics all exceed the EU average, underlining the robustness of the regional industrial base. Nonetheless, in each of these ecosystems, Eastern Slovenia shows even higher levels of specialisation, reflecting its heavier industrial profile.[2]

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) represent an essential driver of regional competitiveness and innovation in Western Slovenia. The region demonstrates particular strengths in product and process innovation, with SMEs introducing product innovations at a rate 56% higher than the EU average, and process innovations slightly above the EU benchmark. The high innovation performance and quality of outputs are also reflected in above-EU scores for employment in innovative enterprises and exports of medium- and high-technology products. Collaboration is another defining strength of Western Slovenia’s SME landscape. Indicators show strong performance in innovative SMEs collaborating with others and in public-private co-publications, underscoring a regional focus on cooperation to foster knowledge transfer and innovation. At the same time, areas for further development remain, particularly in non-R&D innovation expenditure, scientific publications among the top 10% most cited, and PCT patent applications. These highlight the need to further expand the region’s innovation outputs and global visibility.[1]

[1] See ECCP Clusters Meet Regions Slovenia 2025, Input Paper.

[1] (ibid.)

[2] ECCP: Country Factsheet – Slovenia. Berlin, 2024. https://www.clustercollaboration.eu/sites/default/files/2021-12/eccp-factsheet-slovenia.pdf

Although the Northern Primorska Region lies within Western Slovenia (NUTS 2), which demonstrates a strong overall innovation capacity, it nonetheless faces structural and strategic development challenges that hinder its ability to fully capitalise on this positioning.

Like much of Europe, the region faces unfavourable demographic trends, marked by an ageing population and outward migration – especially among young, educated individuals. This persistent brain drain contributes to a weakening labour force and limits the region’s capacity to build and sustain knowledge-intensive activities.

Western Slovenia performs well in transferring research and innovation into economic value. However, in Northern Primorska transfer capabilities are weaker and represent a barrier to its regional competitiveness. Universities, research organisations, and businesses do not collaborate closely enough, which weakens the impact of applied innovation, slows knowledge transfer, and reduces the creation of local career opportunities. The lack of stronger ecosystems for knowledge exchange and technology transfer further limits the region’s capacity to fully harness its research potential.

Historically, Northern Primorska had a robust industrial base, especially in wood processing and furniture production, but the collapse of these industries due to market loss and restructuring left a gap that has yet to be filled with modern, competitive alternatives. While some enterprises in the region are active in niche sectors (such as biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, aviation or the development of hydrogen technologies), they often face resource limitations that constrain their participation in innovation networks and transnational value chains.

Efforts are now underway to reverse these trends, particularly through programmes aimed at retaining young talent and fostering regional innovation ecosystems. However, a core structural challenge remains: the absence of a dedicated regional political entity capable of coordinating innovation policy. As Northern Primorska (Goriška), like all Slovenian regions, lacks political agency, strategic coordination depends heavily on either national or municipal initiatives. In recent years, joint municipal activities have however engaged over 200 SMEs in innovation and transition projects, increased SME participation in EU programmes, and supported regional economic promotion.

Subsequently, the governance structure surrounding regional development in Slovenia assigns a central role to the Council of the Northern Primorska (Goriška) Development Region and the Development Council of the Northern Primorska (Goriška) Development Region, which formally adopted the Regional Development Programme (RRP) for 2021-2027. The document itself was prepared by the North Primorska Network Regional Development Agency (MRRA), by working in cooperation with a wide range of stakeholders from municipalities, businesses, research institutions, and civil society. The RRP defines the strategic orientation of Northern Primorska within the wider Slovenian and European context, highlighting areas of potential such as advanced manufacturing, green technologies, tourism, and biopharma, and thereby serving as a reference framework for both local initiatives and cross-border partnerships.

The RRP also contains an implementation instrument, the Agreement for the Development of the region, which operationalises strategic priorities through project financing. Yet a significant gap emerges here: the Agreement is closely tied to the EU’s cohesion policy and therefore funds activities that correspond to EU eligibility criteria, but not always to the challenges or potentials identified by regional stakeholders. This disconnect illustrates a core limitation of Slovenia’s regional development system. The lack of regional political agency and financial autonomy means that strategic visions often remain only partially realised, as investment follows external, top-down agendas.

A compensatory role for this lack poses also Slovenia’s national Smart Specialisation Strategy. The S4 strategy (2021-2027) introduced a threefold prioritisation model (Healthy living and working; Natural and traditional resources for the future; Nature, values and economic potential) and aimes at aligning national innovation policy with regional needs through structured, inclusive processes. A key instrument in this effort is the entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP), which brought together stakeholders from business, research, and government, including regional clusters, to identify strategic areas of investment and innovation potential.

The updated strategy with a stronger focus on sustainability (S5) was recently published and shows streamlined and more targeted prioritisation framework including nine priority areas:

- Smart Cities and Communities

- Smart Buildings and Homes, including the wood value chain

- Networks for the Transition to a Circular Economy

- Sustainable Food Production

- Sustainable Tourism

- Factories of the Future

- Health – Medicine

- Mobility

- Development of Materials as End Products

The strategy’s development provided a centralised yet participatory platform through which regional stakeholders could engage in shaping national innovation and also strategic funding priorities. By embedding regional needs into national frameworks, the strategy helped mitigate coordination challenges and opened pathways for public–private cooperation, innovation ecosystem development, and talent retention.

Cluster organisations are a cornerstone of Slovenia’s innovation and industrial landscape. They bring together companies, research institutions, policymakers, and civil society to strengthen competitiveness, drive innovation, and support regional economic development.

Slovenia currently counts 21 ECCP-registered cluster organisations, of which 14 are located in Western Slovenia. The regional cluster landscape is highly centralised: 13 of these organisations are based in Ljubljana, with just one situated in Portorož. Compared to EU averages, Slovenian clusters generally have smaller management teams but show similar membership structures, reflecting a landscape that is compact yet highly dynamic. Collaboration priorities are consistent with broader European trends, including internationalisation, project partnerships, digitalisation, and resource efficiency.

Support for cluster activities comes from national calls via EU programmes such as Interreg, Horizon Europe, and COSME, as well as regional co-financing of B2B and innovation events and municipal funding for SME investments. The support is embedded in the Strategic Research and Innovation Partnerships (SRIPs), which are the main implementation instrument of the country’s Sustainable Smart Specialisation Strategy (S5) 2021–2027. SRIPs operate as long-term, mission-oriented partnerships built on the quintuple helix model, bringing together business, academia, government, civil society, and environmental stakeholders. Their purpose is to coordinate joint R&D activities, pool resources, strengthen human capital, and promote internationalisation in nine strategic priority areas of the Slovenian economy. Evaluations confirm their strong impact on improving cooperation, competitiveness, and integration into European value chains.

Currently, out of the 21 cluster organisations in Slovenia registered on the ECCP, the following are government co-funded under the ongoing SRIP funding period:

Slovenian Automotive Cluster (SRIP ACS)

SRIP HRANA – Sustainable Food Production

SRIP ToP – Factories of the Future

SRIP Smart Cities and Communities

These partnerships illustrate the central role of clusters in turning strategic priorities into concrete innovation projects and feeding intelligence back into the Entrepreneurial Discovery Process,refining the S3 priorities over time.

Slovenian clusters are also strongly engaged in cross-border cooperation and European-level initiatives. Cluster organisations from Western Slovenia are active in three ESCP-4i projects and one ESCP-4x project, covering two ecosystems and involving partners from nine countries. They also participated in two Euroclusters under the most recent call, alongside regions from eight different countries, and are involved in one Interregional Innovation Investments (I3) project. In addition, Western Slovenian clusters have taken part in three Interreg projects, with previous involvement in two more, and at least one cluster is also part of Slovenia’s Digital Innovation Hub. These engagements demonstrate how Slovenian clusters leverage international networks to amplify their influence, attract resources, and integrate local actors into European value chains[1].

Conversely, clusters in Slovenia, particularly in northern Primorska, suffer from a culturally and historically rooted image problem. This is largely due to the legacy of poorly managed clusters in the past, which has left a lasting negative perception. At a national level, cluster programmes from the early 2000s were also discontinued after being deemed ineffective. As a result, the term “cluster” is often avoided in favour of “partnership” or “collaboration,” and the notion of clusters as reasonable, future-oriented investments has not been embedded in policy thinking. Despite a legacy of external scepticism, COBIK/BGC and other clusters in the region have managed to overcome these perceptions by demonstrating clear value as policy translators, data providers, and coordinators of innovation consultations. They maintain close contact with SMEs, communicate policy in business-friendly language, and strengthen collaboration through joint projects, partner matchmaking, shared infrastructure, training activities, and events. Acting as trusted intermediaries between convinced businesses and public authorities, clusters provide industry insight for strategy development, coordinate stakeholder consultations, and serve as a first point of contact for SMEs seeking support. They also promote regional assets to investors, organise cooperation both strategically and on an ad hoc basis, and involve regional R&D and industry actors of Northern Primorska in broader initiatives such as the North Adriatic Hydrogen Valley.

Slovenia’s cluster landscape is highly centralised but well aligned with national innovation policies and European priorities. Integrated into SRIPs and active in EU-level initiatives, clusters function both as implementers of the smart specialisation strategy and as connectors to international markets. This relationship ensures that strategic goals are translated into action while embedding Slovenia’s innovation ecosystem in European networks. Going forward, clusters are expected to take on an even more operational role by translating priorities into business action, leading pilot and demonstration projects, and coordinating cross-sectoral partnerships. Their ability to apply for funding as legal entities is particularly important in Slovenia, where regions lack legal status and cannot act as formal applicants.

[1] See ECCP Clusters meet Regions Slovenia 2025, Input Paper.

Biopharma is a specialised branch of the wider biotechnology sector, so the industrial ecosystem is described within the broader biotechnology framework.

Slovenia’s biotechnology sector covers all branches of biotech - including red (biopharma), white (industrial), green (agri-tech), grey (environmental), yellow (food), and blue (marine) biotechnology – demanding expertise across bio-process engineering, microbiology, bioinformatics, and related disciplines. It is a powerful economic driver with high value creation – accounting for over 6% of Slovenia’s national GDP, employing more than 50,000 people directly or indirectly, and contributing around 34% to the country’s exports. National companies invest significantly in innovation, with over EUR 180 million annually funnelled into R&D, compounded by a 15% annual increase in biotechnology patent filings. On the talent side, Slovenia ranks first in the world for the percentage of adults holding doctorates, underpinning also a highly skilled workforce in biosciences[1].

Slovenia’s Smart Specialisation Strategy identifies health and medicine as a key priority, with the explicit objective of establishing the country as one of the global pillars of biopharmaceutical development. This vision is built on close cooperation between large pharmaceutical companies, SMEs, startups, and strong research institutions engaged in translational medicine and therapeutics. The strategy highlights ambitious focus areas, including the development and production of biopharmaceuticals, advanced diagnostics and therapies within translational medicine, innovative approaches to cancer diagnosis and treatment, solutions targeting antimicrobial resistance, and new product lines in natural medicines, dermatological cosmetics, and cell-based therapies. Concrete targets were set to boost exports, stimulate the creation of new companies, and attract foreign direct investment with the aim of strengthening competitiveness and generating high-quality jobs in the health–medicine domain[2].

Beyond the national level, Slovenia’s biopharma ecosystem is embedded in the wider Central European innovation space, with complementarities to neighbouring regions such as Friuli-Venezia Giulia’s biotechnology and biomaterials expertise or Croatia’s strengths in life sciences and biomedicine. Joint initiatives in fields like oncology research, protein antibodies, and advanced biomaterials demonstrate the strong potential for cross-border collaboration and integration into European innovation networks.

However, new actors in Slovenia’s biopharma sector face major investment challenges, particularly in bridging the gap between early-stage public funding and the substantial capital required for later development stages. Many projects originate from mostly publicly financed research and can progress to around Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 5, the starting point for pre-clinical work. Beyond TRL 5, costs rise sharply due to the onset of clinical trials, with expenses for regulatory compliance, specialised equipment, high-grade materials, and fully equipped laboratory facilities far exceeding those in sectors such as IT, AI, or electronics.

[1] Slovenia Biotech Hills: Slovenia - The future of biotechnology research, innovation, and production in Europe. Ljubljana, 2024. https://www.biotech-hills.si/

[2] Slovenia’s Smart Specialisation Strategy S5 (2022). https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MKRR/Slovenska-strategija-trajnostne-pametne-specializacije-S5-marec2022.pdf

COBIK & BIOPHARMA GLOBAL CONNECT CLUSTER (BGC)

Recognised with the Bronze Label for cluster management excellence, COBIK – the Centre of Excellence for Biosensors, Instrumentation and Process Control – and its cluster extension, the Biopharma Global Connect Cluster (BGC), brings together scientific excellence, entrepreneurial spirit, and international partnerships to advance biotechnology and biopharma in Slovenia and beyond.

Established in 2009, COBIK acts as a leading Slovenian research hub that brings together scientists and industry to tackle health challenges such as antibiotic resistance and new infectious diseases. It develops advanced bioprocesses and produces essential biomolecules like proteins, DNA, and vaccines. COBIK also supports companies and researchers with project management, regulatory advice, and access to modern laboratories in its state-of-the-art facility in Ajdovščina. Beyond medicine, its work extends into food, environmental, and agricultural biotechnology, making it relevant across several sectors. Through collaboration, innovation, and knowledge transfer, COBIK strengthens Slovenia’s role in the European and global biotech landscape.

To expand this role, the Biopharma Global Connect Cluster (BGC) was launched in 2021 as a specialised spin-off initiative within COBIK, designed to take on network-oriented tasks and provide targeted support for ambitious biotechnology projects in biopharma, food, environment, and agriculture. BGC guides participating partners across all stages of development, helping to translate ideas into market-ready applications while strengthening competitiveness, fostering collaboration, and linking regional actors to global value chains.

BGC’s origins trace back to informal partnerships formed before COBIK’s establishment, when entrepreneurs and researchers in Slovenia’s Vipava region set out to develop a smaller-scale version of innovation ecosystems like Silicon Valley. Their strong local commitment, combined with the ambition to achieve globally relevant breakthroughs in biopharma and biotechnology, laid the foundation for COBIK. Today, COBIK serves as BGC’s institutional and operational backbone, ensuring continuity, credibility, and international orientation. In 2017, COBIK received the Bronze Label under the European Cluster Excellence Initiative (ECEI), recognising its formalisation and strategic coordination efforts.

BGC nowadays optains funding through two principal sources: The United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO), which supports the cluster as part of its broader mandate to enhance industrial cooperation and technological development among emerging economies, and the Slovene Enterprise Fund (SEF), which contributes national innovation funding to support internationalisation, entrepreneurship development, and cluster-based cooperation.

Within COBIK, BGC is managed by a core team of two full-time equivalents (FTE), however most of the cluster’s service outputs are generated through collaborative cluster initatives like R&D projects. BGC does not charge membership fees and, instead, sustains its activities through public funding and chargeable services, offering its open partner network support in project development, financial administration, and R&D as a service, particularly for startups and scale-ups in the biopharmaceutical and cellular agriculture sectors. Today, BGC comprises over 30 partners in Slovenia and an additional 50–60 international partners, including key strategic players such as the Cuban biopharmaceutical group BioCubaFarma. This global orientation reflects BGC’s broader focus beyond pharmaceuticals – its scope extends into biotech for environmental, food, and the prevention of diseases in agriculture.

While COBIK provides development of challenging bioprocess workflows, non-GMP manufacturing capabilities and complete project management expertise, BGC’s strategic priority is to help regional innovation actors to commercialise their ideas and connect them to the global market. Its overall objective is to enable the development of biopharma products that require specialised ecosystems (for knowledge transfer, R&D services, equipment, etc.) and long-term investment strategies. The network thus provides tailored one-on-one support to its partners across the innovation cycle – from identifying funding mechanisms and writing proposals to managing R&D and navigating regulatory processes. Its positioning at the intersection of a cluster, incubator, and innovation platform allows BGC to act as afacilitator of both scientific development and market readiness. Through these activities, BGC contributes to building a wide-ranging ecosystem with the aim to attract critical investment and accelerating the path from idea to the lab to market. The network operates through four functional working groups (focussing on capacity building in regulatory acpects, internationalisation, competences as well as transfer with the help of the virtual biotech incubator):

Regulatory Aspects

- The working group for regulatory topics is responsible for supporting the cluster and its members with regulatory guidelines and for preparing suggestions for the harmonisation of Cuban and EU regulatory guidelines.

Internationalisation

- The working group for partnerships, international relations, and fund mobilisation is responsible for promoting the cluster and cluster projects outside the cluster, raising funds, including EU projects; attracting investment; recruiting new potential members willing to join the cluster, and marketing strategies.

Competences

- The working group is responsible for the identification of needs for training, workshops or study tours.

Virtual Incubator

- The working group is responsible for supporting cluster members on new business projects, promoting start-ups, supporting the adoption and transfer of advanced biotech, and supporting the adoption and transfer of advanced applied digital technology.

With these focus areas, BGC is designed to provide support oriented to the full innovation circle – from concept through development to market launch.

An early attempt to address the investment gap in the biotechnology sector was the creation of the co-investment platform COINVEST in 2013, which aimed to connect promising biopharma projects with specialised investors. However, the platform was hampered by a limited number of projects that were sufficiently mature for investment, as biopharma development cycles are long. This constrained deal flow forced COINVEST to broaden its scope into other innovation fields, whilst the withdrawal of public funding in 2016 also brought an end to large networking events. Today, investment matchmaking takes place mainly on a one-to-one basis, but attracting significant capital remains challenging.

Additionally, BGC is strongly involved in the flagship initiative of the Biotechnopolis in Ajdovščina, which is part of the broader Knowledge Park. BGC and COBIK are expected to play an essential role in one of three pillars (next to aviation, and hydrogen). The main task will be the establishment and operation of a specialised biotechnology incubator in the fields of biopharma, environment, agriculture, and food, positioning Ajdovščina as an excellent entry point for any project in these areas, regardless of its TRL development stage.

COBIK played an active role in the development of Slovenia’s national Smart Specialisation Strategy (S3) through the Strategic Research and Innovation Partnership (SRIP) ‘Health and Medicine’. Within this framework, biopharma has been established as one of the three strategic pillars of the Medicine and Health domain.

Through this involvement, the cluster not only benefited from the SRIP’s role as a central institutional mechanism – providing knowledge, networking opportunities, and support for project documentation – but also fed into the broader policy and investment priorities set by the S3. This integration ensures that the biopharma cluster’s innovation needs and development potential are aligned with national strategic objectives, enabling better access to resources, fostering cross-sector cooperation, and enhancing regional capacity to compete in global health and medicine markets.

Moreover, COBIK has played a central role in advancing Slovenia’s health and medicine priorities by initiating two major projects, Biopharm.si and Smartgene.si, and assuming the lead in one of them. Both initiatives represent concrete implementation of European funds allocated through Slovenia’s national Smart Specialisation Strategy (S3). Partners of the COBIK-operated BGC network are directly involved in these projects, which serve as key platforms for strengthening cooperation between research and industry and for positioning Slovenia within European health innovation networks.

- SmartGene.si was a EUR 4 million project completed in 2021 that developed innovative, globally applicable solutions for gene therapy, including novel cancer treatment approaches, advanced plasmid DNA production, and a state-of-the-art certified production facility for medicines, significantly enhancing Slovenia’s capabilities in translational cancer research.

- BioPharm.Si is a close to EUR 9 million national programme bringing together leading Slovenian companies and top research institutions to develop continuous biotechnological processes for producing complex biological medicines such as proteins, DNA, and vaccines. By advancing equipment, processes, and services for continuous production, it aims to increase productivity, lower costs, and enhance flexibility in biopharmaceutical manufacturing.

LESSONS LEARNED and TRANSFERABILITY

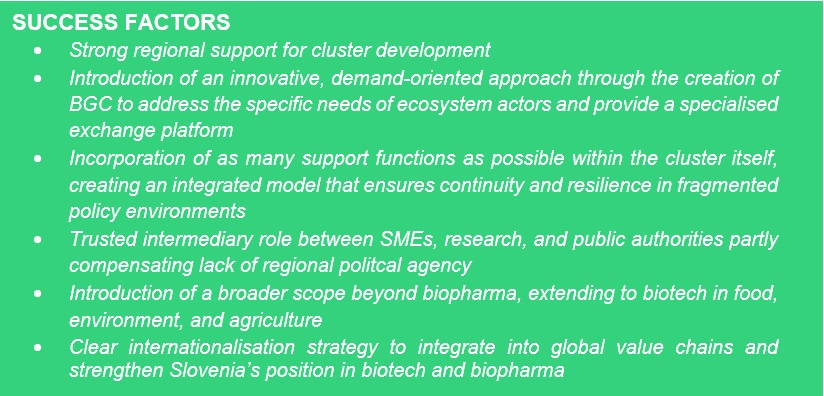

The experience of COBIK and BGC highlight how the structural configuration of a regional innovation system can decisively influence a cluster’s trajectory – especially in sectors such as biopharma, where development cycles are long, costly, and high-risk. Unlike clusters in industries with strong industrial bases and predictable supply chains (e.g. automotive), biopharma requires decades of sustained investment, interdisciplinary collaboration, and navigation of complex regulatory frameworks.

To cope with these conditions, BGC has adopted an adaptive, self-contained model. The network internalises many ecosystem functions, acting simultaneously as a biotech incubator, R&D service provider, regulatory advisor, and internationalisation platform. This integrated approach reduces dependency on fragmented public programmes, ensures continuity, and safeguards knowledge transfer across projects and generations.

The case of BGC also underscores the importance of perception in cluster policy. Earlier failures of cluster initiatives in Slovenia created a legacy of scepticism that still influences political and cultural attitudes. Overcoming this stigma requires more than promotional efforts; it depends on delivering measurable impact that convinces policymakers, industry, and the wider public of the strategic value of clusters.

Against this backdrop, BGC demonstrates the broader role clusters can play in Slovenia’s innovation landscape. Nationally, clusters act both as co-designers and implementers of the Smart Specialisation Strategy and as bridges connecting Slovenian actors to international networks. Going forward, their responsibilities are expected to expand further, translating strategic agendas into business action, leading joint projects, and coordinating (cross-)sectoral cooperation. This role is particularly significant in Slovenia, where regions lack legal status and cannot directly apply for funding.

Transferability of the BGC experience lies in three main lessons: First, clusters in long-cycle, high-risk sectors require funding frameworks adapted to their timelines and investment patterns. Second, demand-oriented cluster models that combine multiple ecosystem functions under one roof can be effective in overcoming fragmented policy support. Third, narrative matters: success stories backed by clear value are essential to rebuild trust in clusters as strategic, future-oriented investments.

With adequate financing, deeper integration into governance structures, and stronger roles in data provision and policy monitoring, clusters like BGC could become key instruments in addressing systemic challenges and unlocking the full innovation potential of regions such as Northern Primorska.